I love airships. Unhealthily. There, I said it. I think they are beautiful. They float. Ever since doing Physics ‘A’ level I’ve been unhappy with planes, and to this day I always have a few medicinal beverages before embarking on a journey in one. Airships have no such fear for me, since they float. Just take a moment to realise that. Float. Hang, in the air.

But, I hear you cry, airships were always a dead-end technology; people knew at the time they weren’t going to last; they are of no use; they were stupidly expensive; they were dangerous; and anyway, they don’t exist any more – what’s the point of being in love with something which last flew nearly eighty years ago?

Well, it might be a struggle, but why don’t we go through these and explore them a little, and maybe you can join me in my affection for the giant flying… machines? No, they are not just machines. Let me put in the words of the Zeppelin commander, second to none.

Hugo Eckener in 1924

What is a Zeppelin airship?

It was not, as generally described, "a silver bird soaring in majestic flight," but rather, a fabulous silvery fish, floating quietly in the ocean of air and captivating the eye, just like a fantastic, exotic fish seen in an aquarium. And this fairy-like apparition, which seemed to melt into the silvery blue background of sky, when it appeared far away, lighted by the sun, seemed to be coming from another world and to be returning there like a dream... emissary from the "Island of the Blest" in which so many humans still believe in the inmost recesses of their souls.

Dr Hugo Eckener

OK, that’s quite something, so let’s see if we can back it up.

Let’s go through our issues with the airship one by one, and maybe we’ll see how they could have been around for me to enjoy. This will involve a little bit of changing history, but…

“It was a dead-end technology.”

True. There, I said it. Happy now? Well, dead-end means a multitude of things. Flying boats were dead-end technology, milkfloats were dead-end, steam trains were dead-end, sailing boats were dead-end technology, cassette tapes were, video recorders were... The dead-end nature isn’t the point. Almost everything we have now has a lifespan. The question is was it useful while it lasted. For that I realise my argument is hard, because you immediately say that airships weren’t. But you’d be wrong. They were. They were very successful. Just not in the way you’ve heard of.

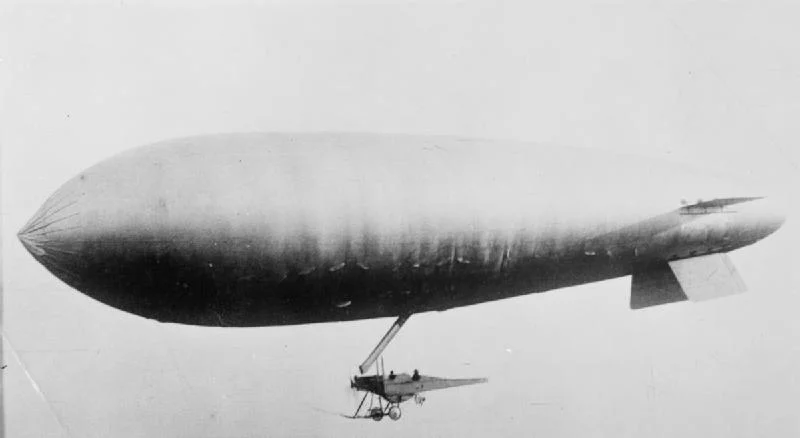

Britain had a large fleet of airships. Not zeppelins, but definitely airships. Zeppelins, by the way, have a rigid superstructure, which gives benefits we’ll come to later, but for now, leave it at that. Blimps are pressurised bags of hydrogen or helium which keep their shape only under pressure. Anyway, that’s the technical bit. On to why Britain had its fleet.

A U-boat is almost impossible to see from the surface of the ocean. It is, on the other hand, rather easier from a few hundred feet above, where the problems of diffraction are lessened (due to the angle of the light being closer to perpendicular, obviously – physics ‘A’ level does give you some things other than just a fear of aeroplanes). However, heavier-than-air (HTA) aircraft can’t easily stay airborne for long enough to help with a convoy of ships. So, airships floated above vessels on the surface and warned them of approaching submarines. In fact there was even an unsubstantiated airship-on-submarine in the second world war (US airship). Airships could remain aloft for many hours at the same speed as the fleet below without problems.

When the US was evaluating its zeppelins prior to the second world war (the Akron and the Macon), they were repeatedly given little chance to succeed. They were each supposed to be scouting vessels, carrying six to eight small planes and launching them out from either side in a giant scouting pattern, covering enormous areas. In the event they were either tested in wargames with the enemy close by, or without their complement of scouting planes, or with the ‘enemy’ knowing their location. Brief glimpses of success appear within the gloom, but one disaster cost a lot of the expertise, and the next disaster put paid to the programme. There had even been a bill passed to create a new fleet of six airships to keep the programme going, but the untimely death of a senator brought an early end to a session of congress (out of respect) and the bill wasn’t reintroduced. The US came close.

“People knew at the time they weren’t going to last”

I have heard tell that people knew, deep down, that HTA would always win out, but even when people quote sources at the time, they aren’t necessarily referring to the same thing. One example is that Jules Verne wrote a story called Robur the Conqueror, in which the eponymous Captain Nemo lookalike Robur kidnaps people in his HTA craft and carries them round the world before the craft suffers a major disaster. To readers aware of the Nautilus it may sound familiar, although at least it is missing the descriptions of fish. However, on closer examination the Albatross, the Nautilus looky-likey, isn’t your average air-conqueror. It hovers. It uses screws to hover. At first glance it looks a little like the flying platforms in Sky Captain, or the SHIELD flying helicarrier, but using screws rather than propellers. It hovers and shoots down the airship Go-Ahead in the story. It uses electrical power stored in a special way that only Robur knows. And generated from somewhere mysterious. I suspect it’s a nuclear-powered aircraft, if anything. But effectively it is acting as lighter-than-air (LTA), since it can maintain a constant position. Not even like the madness that is a helicopter, no – it just hovers and then had sideways screws for propulsion. Mr Verne did not know how HTA would win, much as he assumed it would.

And don’t get me wrong – I know we couldn’t get to San Francisco in a day using an airship. I know jet engines are amazing things, much as they scare the bejeezus out of me.

But jet engines weren’t around when people were saying how stupid LTA was. Jet engines came along as part of the genius employed by the British to try to remain standing during a life-or-death struggle. If that struggle hadn’t happened, only prop-driven planes might be around, even a few decades later. Bear in mind that the first non-stop HTA service from Europe to the US was in 1958. By airship, three decades earlier. Plus it didn’t take much more time to go direct by airship than it did by plane for most of that time. The aircraft had to stop over and refuel in each stopover point, making the whole journey well over a day, whereas the airship managed it in two, and with comfort. There was even a regular service to South America from Hamburg taking three days when few ocean liners even bothered to go south.

“They are of no use.”

I’ve mentioned scouting. I’ve mentioned passenger services. I suppose I could shoehorn the Goodyear blimp in here, but I’m not going to.

The US maintained a fleet of airships until satellites took them out of service. That’s 40 years of being of no use. The idea of using them for communications as a midway point between cells and satellites still occasionally gets a hearing. The idea of using them for carry cargo, bulky or otherwise, to remote places where airfields aren’t available – that also comes up over and over again. The problem has always been that the prototype stage was never passed.

The R34 was the first aircraft of any type to travel the Atlantic east to west, and the first to travel west to east and actually land safely rather than in a bog in Ireland. The Graf Zeppelin set so many records it’s hard to list them all. It flew a million miles, including a round-the-world trip. It flew to the arctic and exchanged post with an icebreaker there. It flew to South America numerous times. It led its captain, the aforementioned Dr Eckener, to get no fewer than three ticker-tape parades in New York. How many did Neil Armstrong get? Just saying. It was a matter of a hundred miles away from having had the only chance any aircraft ever got to view the Tungaskaya event in Siberia from the air before it was grown over. If only, I know. There are many of those.

It may be worth dropping in here that prior to airships aeroplanes were wooden. The lightweight duraluminium was developed for them, and allowed metal planes later on. Just in case anyone thinks their developments were pointless. Oh yes, and the R100 was designed by Barnes Wallace, cutting his teeth on design before going to do develop the bouncing bomb and the Lancaster bomber a few years later.

“They were stupidly expensive.”

They were. There, you see – I can say all these things. But hang on just a minute – compared to what?

A flying boat when it began service from the US to the UK hopping as it did around the Icelandic coast cost something approaching a quarter of the price of the Hindenburg, and that was when they were beginning to be built in numbers. They carried fewer people. Airships never quite got the go-ahead into the numbers game to reduce the costs.

The US navy believed that the real cost of building an operating a rigid-framed airship of the size of the Macon or Akron was about the same as building a cruiser, and bear in mind that a cruiser could be destroyed by dive-bombing just as easily as an airship, if located by the enemy while isolated from a fleet, such as on a scouting mission, and didn’t have anything like the range or speed.

If you were talking orders of magnitude difference for a like-for-like solution, I might agree, but while the British certainly wasted immense amounts on the R100 and R101, the waste was because they didn’t test properly and evaluate prior to actual flights, and if you had stopped HTA programmes at the same period you’d have found the same discussions after the fact. If the first Concorde had failed to get a safety certificate, for example, or the crash had been earlier, who knows?

“They were dangerous.”

A million miles, the Graf Zeppelin flew. No one was injured. The US lost three airships, but in all a matter of a bit over a hundred people. The Hindenburg, always the poster child of the dangerous airships club, saw two-thirds of the people on board survive bursting into flames above an airfield. How many HTA craft could boast such a survival record?

In fact, when you compare like-with-like again, you’ll see that the HTA craft were regularly crashing, leaving rich widows to inherit fortunes as their playboy husbands perished, but they had the decency to do it away from the cameras, and usually left little or no wreckage to pore over the next day. Even decades later you have the series of Comet disasters, the DC-10s, and even the great US bomber the B52, which simply split apart when stressed. The difference was that the airships didn’t quite get enough numbers behind them to make it clear the statistics. One craft flew out of Germany for almost a decade before it was joined by a sister ship – imagine how sad the poor Graf Zeppelin was to be alone for so long. The UK tried two. The US tried three. In each case they were just gaining the experience when they stopped. Apart from Germany, where they sacked the experience because it wasn’t Nazi enough. Probably not Hitler’s worst crime, I admit.

The hydrogen issue ought to be raised here, I suppose. Hydrogen is highly flammable, but whatever is inside the gasbags, if the gasbags themselves are flammable you are asking for trouble. And diesel fumes in empty fuel tanks are far more flammable, and caused numerous explosions on HTA craft before they began pumping inert gasses into the empty tanks. Documents leaked from the Zeppelin company showed that they changed their outer covering radically after the Hindenburg, having developed it new for that ship. A man called Upson developed a metal-clad airship (the ZMC2) in the US in the 1920s which, it was believed, solved the problem by simply making a properly non-flammable material entirely surround the gas. There was even an article on the subject in the “Wayne Engineer” arguing the case between the fireproof gas or the fireproof airship.

It may also be worth a small digression to the time of the Spanish-American war, when repeated US battleships had exploded, possibly due to the coal store being next to the magazine. They spontaneously exploded – not even when under fire. The USS Maine was destroyed this way, as was the USS Oregon. Again it’s a matter of numbers. The stupid mistakes can be learnt from as long as there is enough quantity to make the learning possible.

Just compare that briefly to early world war one zeppelins where bullets could rip through them over and over again, but because they were at air pressure (because the rigid superstructure meant the bags didn’t need to provide shape) the leakage was still fairly low, and they did not burn until the British designed the tracer bullets which set fire to… the outer covering.

“They don’t exist any more – what’s the point of being in love with something which last flew nearly eighty years ago?”

I suppose this is the hardest to answer in any sane way. Despite recent possible zeppelin developments (and yes, I do get excited whenever a news story appears about them), they are dead. The Science Museum in London describes them as “Dinosaurs of the Sky”. I don’t honestly hold out hope they would reappear in any meaningful sense.

But just for a moment imagine that giant ship simply hanging there, as Douglas Adams once remarked “in the exact same way that bricks don’t.” Imagine it floating, like a spaceship visiting Earth in a 1950s B-movie. Imagine it gliding by, almost noiselessly. It’s the gentle giant in harmony with the sky while a plane thrusts up into the sky, imposing man’s will upon it. The airships simply navigated around storms to use their winds to help their speed. Up to date meteorological data would have helped no end, it has to be said, and would have saved at least two of the 1930s disasters.

I have a picture above my desk at work of the Arsenal v Huddersfield Town FA Cup final match at Wembley stadium in 1930. Arsenal won 2-0, if you care. It was their first trophy. Again, if you care. Above them flew the Graf Zeppelin, floating above the pitch for a short while before disappearing again. The people on board could see the game clearly, and a few people bothered to look up. Not all of them even noticed what was hanging above them. Hanging.

One of the reasons people scuba dive is the intense feeling of calm as you hang in the water and things can float past you. Imagine that same feeling, but now with a craft vastly bigger than the biggest airbus now flying. At peace with gravity.

I rage against the past, and I will accept, at this late stage, that this doesn’t do me any good; nor is it entirely sane. But I will continue to rage against the past that didn’t leave me a handful of enthusiasts still running a last couple of zeppelins that I could go and fly on. Just once. Just to feel the lack of wind beneath my wings, to be able to open the windows and feel the coldness of the air.

All it would take is one Russian billionaire to decide not to lavish money on overpaid journeymen from the four corners of the globe who happen to be wearing the same coloured shirt as you this week but instead to spend that money on producing a folly – yes, I know it would be a folly – but surely a folly which would leave more of a lasting impression than “Oooh, look, Chelsea are in with a shout this season” as it glides magnificently over the London skyline?

I can but hope.