The story of Wojtek (pronounced Voy-tek) the soldier bear should be better known than it is.

The basic story is that the Persian bear was adopted by a company only recently released from a Russian gulag after Stalin released the Poles when the Soviet Union was attacked by Hitler, and Wojtek took to them so much he became effectively tame and helped carrying ammunition in the battle of Monte Cassino, one of the hardest battles of the journey up Italy.

When the Poles reached Britain at the end of the war, they were popular for a time, but faced trouble later. I feel this resonates with now, and would like to quote two passages from the above book. It is worth bearing in mind that the Polish memorial in Canada adds two extra words to the list of battles fought by Polish soldiers, so valiantly in the cause of the Allies: "YALTA" and "BETRAYAL", referring of course to the willingness of Churchill and Roosevelt to abandon their allies at the end of the war.

As the book says:

"These people complained about our presence in Britain and tried to persuade the government to quickly repatriate us, even though Winston Churchill had previously made a speech in which he acknowledged Poland's vital contribution to the war and that her 'exiles' should be given U.K. citizenship. Incredibly, many British people actually believed that we were the problem, not Stalin! They wanted us to be sent back to Poland as soon as possible. This antagonism continued in other unpleasant ways for years afterwards too. For those of us who stayed in this country after we were demobbed, it was very difficult for example in the early 50's when we eventually left our 'Polish Person's Displacement Camps' to buy our own homes.

"It was not uncommon to see signs with 'No Poles; no Irish; no Blacks' attached to 'For Sale' signs. It seems unimaginable in the current politically correct climate and added to the hardship suffered by so many Poles (and others) who had been deemed good enough to help the Allies during the war, but not now to make a home here. We were prepared to work hard and honestly, so we really didn't understand what the problem was."

Another section reveals just how hard they were prepared to go to fit in, despite the above, talking about their Polish clubs:

"These weren't 'closed' to everyone other than Poles by any means. Wherever you live, you have to integrate for the good of society as a whole, though there is no harm in keeping and nurturing your own identity and culture within that society (in fact it is important to do so) though without trying to enforce it over and above that of the host country. Added to that, is the need to learn the language of the country in which you live, part of the process of integration. I believe it is also essential to share and explain one's beliefs and cultures with others in other to promote better understanding and therefore tolerance. In my personal opinion, these are vital and achievable objectives for a truly successful multicultural society.

"Our English friends, including local V.I.P.'s, have also always been invited to social events; in fact at our club for example, an Anglo-Polish society was formed many years ago which used to meet there regularly, its members enjoying a Polish beer or glass of wine in the bar downstairs after monthly meetings. Our restaurant and continental food shop have also always been popular with Polish, English, Irish and Italians alike; quite cosmopolitan!"

My father-in-law came over from Poland (although was originally from Austria-Hungary) with other Poles after the war, and I know another elderly Pole who survived the gulags, but lost his father there, and fought for the Allies and was even decorated, so I feel a certain connection. It saddens me that many Poles were convinced to go home, only in many cases to be imprisoned and often shot on their return.

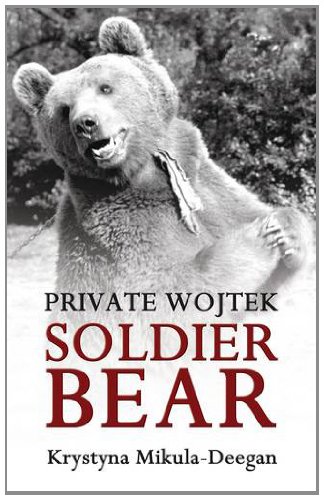

However, the story of Wojtek is funny, and beautifully told, and heartily recommended. Pick up the book. And if you still need convincing, here's a picture of Wojtek, not yet fully grown.